Videotext

In 2004, Dr Eckart Köhne from the Constantine Exhibition Society and archaeological surveying specialist Martin Schaich from the company ArcTron 3D GmbH in Altenthann near Regensburg developed a bold idea: the various fragments of the colossal statue of Constantine in Rome were to be documented in three dimensions using a combination of archaeological research and innovative high-tech, and partially reconstructed and reproduced for the state exhibition in Trier.

In this way, one of the world's most famous monumental imperial statues from Roman antiquity could be experienced in a new way during the exhibition. With the support of the Landesbank Rheinland-Pfalz, the Landesbausparkasse and Provinzial Versicherungen, we were able to begin this unique and ambitious project in 2005.

Rom. The world-famous colossal fragments of the statue of Constantine stand in the inner courtyard of the Capitoline Museum (Photos: ArcTron 3D GmbH).

In this way, one of the world's most famous monumental imperial statues from Roman antiquity could be experienced in a new way during the exhibition. With the support of the Landesbank Rheinland-Pfalz, the Landesbausparkasse and Provinzial Versicherungen, we were able to begin this unique and ambitious project in 2005.

After his victory at the Milvian Bridge in 312 AD, Constantine the Great commissioned a monumental statue of himself. The 12 metre high work was erected in the new basilica between the Roman Forum and the Colosseum, which his opponent Maxentius had had built.

With this statue, Constantine took the place of his defeated adversary for all to see.

The monumental fragments, which weigh several tonnes and were discovered in Rome in 1486, could not be loaned to Trier for the exhibition as they have stood in the courtyard of the Capitoline Museum for more than 400 years. Due to the delicate marble surface, a traditional moulding with silicone for a reproduction was also not possible.

The surveying specialists from ArcTron 3D therefore documented the statue elements with non-contact 3D scanners on site in Rome. In addition to a 3D laser scanner, a high-resolution structured light scanner was used to capture the objects in three dimensions with accuracies in the tenth of a millimetre range. Some of the work had to be carried out at night, as this is when the structured light projection is least affected by extraneous light.

The various 3D scans - a total of around 1000 scans were realised - were put together on the computer in a process that took several weeks.

Each individual scan consists of a point cloud with several million measuring points that precisely describe the surface geometry.

Special computer programmes are used to convert the point cloud into a close-meshed, highly detailed triangular grid. Finally, a photorealistic surface is applied to the mesh structure.

Archaeologists now have a variety of new opportunities to study the ten preserved parts in detail and with the utmost precision on the computer. In addition to the almost 3 metre high head and the two feet, several parts of the right leg and the right arm, a hand as well as a breast fragment and one of the temple curls have been preserved.

The 3D models were analysed in the ArcTron software aSPECT 3D, which is specially developed for 3D documentation in archaeology, heritage conservation and restoration.

For the scientists involved from Rome, Trier and Regensburg, this formed an ideal basis for determining the positioning and composition of the complex 3D puzzle in more detail from an archaeological and structural point of view.

Parts of an older statue were used for the colossus. Reworking, differences in proportions and other observations suggest that an older statue of a god or emperor was reworked and reused here.

When the statue was erected in antiquity, the individual parts of the enormous monument had to be fitted together precisely using the interlocking and joining techniques available at the time.

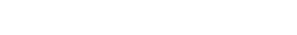

The result of our reconstruction is visible in a partially transparent representation, in which only the preserved fragments are shown as solid bodies.

For the scientists involved from Rome, Trier and Regensburg, this formed an ideal basis for determining the positioning and composition of the complex 3D puzzle in more detail from an archaeological and structural point of view.

Parts of an older statue were used for the colossus. Reworking, differences in proportions and other observations suggest that an older statue of a god or emperor was reworked and reused here.

Bei der antiken Aufstellung der Statue mussten die einzelnen Teile des gewaltigen Monuments passgenau mit den damals möglichen Verklammerungs- und Verbindungstechniken ineinander gefügt werden.

Das Ergebnis unserer Rekonstruktion wird in einer teiltransparenten Darstellung sichtbar, in der nur die erhaltenen Fragmente als massive Körper dargestellt sind.

From the rough 3D sketch with integration of the original fragments to the coloured reconstruction of the colossus. (Graphics: ArcTron 3D GmbH).

The reconstruction also makes it clear that the ancient sculptors realised a technical masterpiece here that could only be recreated with great difficulty, even with today's technology. The individual parts of the colossal statue, which weighed several tonnes and were around 12 metres high, were fitted together with millimetre precision like a ‘3D mosaic’ on a solid wooden frame, thus giving the ancient viewer the illusion of a uniformly compact figure. The statue was made of different materials. The unclothed parts of the body were made of marble, while the gold-coloured robe and the attributes in the hands were made of bronze. Also important for the appearance is the fact that the ancient statues were generally painted and thus conveyed a completely different impression than we would expect with our marble-focussed visual habits today.

Our Constantine Colossus integrated into the current reconstruction of the Maxentius Basilica at the University of Virginia (Graphics: ArcTron 3D GmbH & IATH, University of Virginia).

The exact location of the statue in the Basilica of Maxentius has been preserved in Renaissance drawings that show the base of the pedestal in the apse on the narrow side of the building. We can now experience the statue in an interior model of the basilica from the perspective of the ancient observer. ArcTron also offers a 3D virtual reality environment for this, which allows such objects to be visited interactively with 3D glasses.

The copy of the colossal head

To produce the 1:1 copy in marble

But how was it possible to create the detailed marble copy of the Constantine head, which is almost 3 metres high and weighs 6 tonnes? In cooperation with the companies ArcTron 3D (Regensburg), the Fraunhofer Institute (Berlin) and Prometheus GmbH (Berlin), a process chain was developed and realised under the project management of sculptor Kai Dräger, in which a highly precise marble copy of the head was created, which can now be admired in the exhibition.

The block for the marble copy was ‘sought and found’ in the famous Italian marble quarry of Carrara (Photos: Kai Dräger, Prometheus GmbH).

A suitable block of marble was first selected in the quarries of Carrara in Italy and this stone, weighing around 25 tonnes, was transported to the Frankenschotter company in the Altmühltal. The profiles were cut out using a computerised wire saw, which significantly reduced the amount of material required for the subsequent milling process. The journey now continued to Schönberg near Kiel. EEW, a company specialising in the construction of high-tech milling machines, took over the further processing there.

A state-of-the-art 5-axis CNC milling machine was used, which was able to machine a marble block of this size: another technical world first.

After the rough cut with the contouring, the 5-axis high-tech CNC milling machine at EEW in Kiel-Schonberg took over the finishing of the head (Photos: Kai Dräger, Prometheus GmbH).

From the distinctive nose to the complex hair structure: in order to copy the original exactly, the machine had to run different cutting, drilling, roughing and finishing programmes during its 520-hour operation. To do this, the computer data was converted by DELCAM into a format that could be read by milling machines. More than 230 different programmes and special tools were developed for these complicated processes.

Klel and Berlin After the milling process, the head was reworked and ‘artificially aged’ in the sculptor's studio (Photos: EEW Maschinenbau GmbH / Kai Drager, Prometheus GmbH).

In the end, the new Constantine looked very similar to the Roman original! Sculptor Kai Dräger has now put his hand to it again in the large-scale studio in Berlin: using traditional tools and a special restoration process, he worked on the stone so that the surface came as close as possible to the original, which had been marked by the ‘ravages of time’.

all roads lead to Rome ...

At the beginning of May, the marble copy was transported to Trier with the specially built steel substructure. A special crane then lifted the head to its place in the State Museum. After the exhibition in Trier, the marble head will start its journey to Rome. The Capitoline Museums now have the option of replacing the original head in the courtyard, which is threatened by exhaust fumes and other environmental influences, with the copy, although a decision on this is still pending. It would be a big step to remove the original from its pedestal after 400 years.

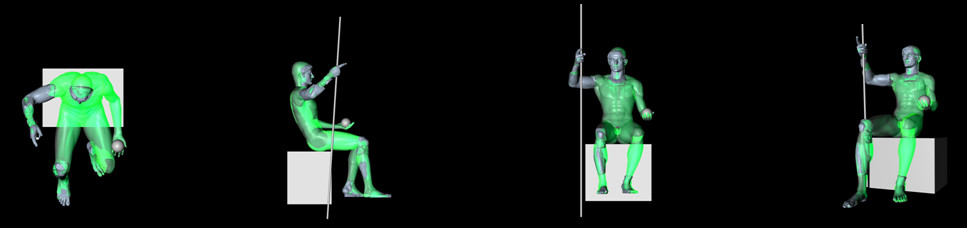

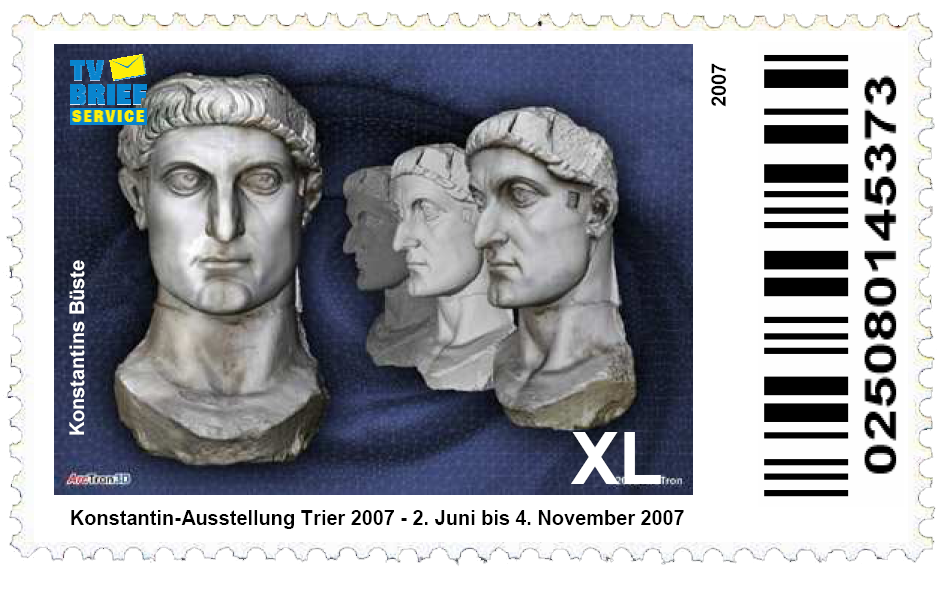

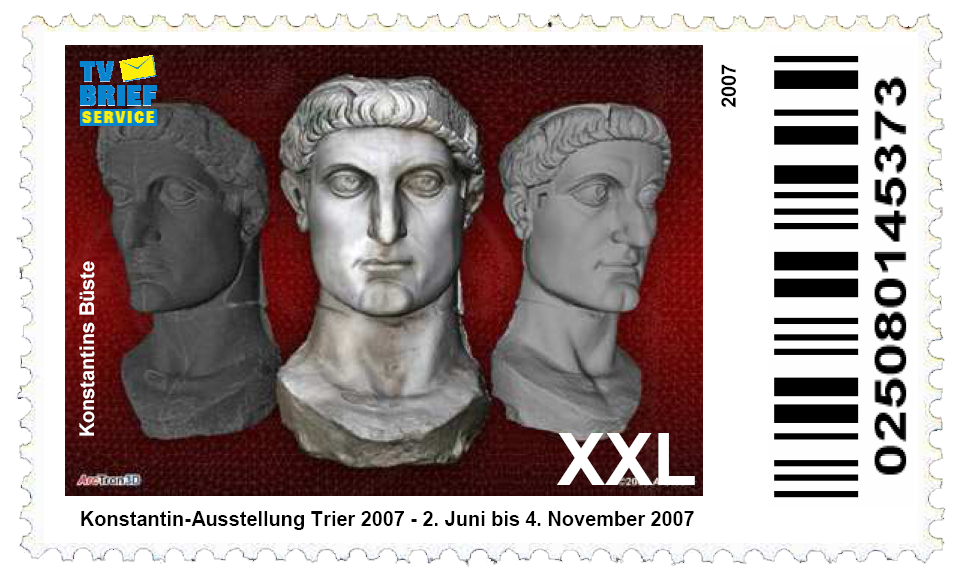

From 3D scan to stamp

Our 3D graphics were so popular that we even created a small series of Constantine stamps on this theme.

(Grafiken: ArcTron 3D GmbH)